Posted by Buffalo Games on Jun 28th 2022

Charles Wysocki Puzzles: An American Original

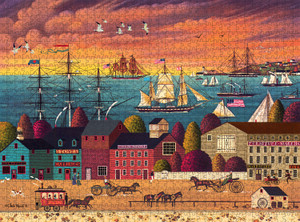

If you’re looking for your next puzzle at the puzzle store and feel that a little whimsy could do you good, look no further than our offerings from Charles Wysocki. We’ve got everything from 300-piece puzzles to 1000-piece puzzles and more — all featuring Wysocki’s classic folksy art.

You’re going to love his simple take on the Americana of yesteryear. The clean lines of his paintings lend themselves very well to jigsaw puzzles for adults, which is why we carry so many different jigsaw puzzles featuring his work.

Who Was Charles Wysocki?

Born in Detroit, Michigan, Charles Wysocki, Jr. was born in 1928 to Charles and Mary Wysocki.

Charles Wysocki Jr. studied art at a technical high school in Detroit. He was drafted into the army in 1950 and spent a few years in West Germany. When his time in the Army was up, he attended art school in Los Angeles through the GI Bill, studying commercial illustration.

There is no evidence that he was an expert at jigsaw puzzles, but his work would certainly show up in countless jigsaw puzzles for adults and kids in the years to come.

In the 1950s, commercial illustration was a big career. If you’ve ever seen advertising from the 1950s, you know that everything from coffee makers to cars and sewing machines was sold based on how artists depicted the products they drew.

In particular, cars were always drawn a little lower, longer, and wider than they actually were in real life. As a result, due to their added presence in the artist’s illustration, they drew more people to the showrooms to see them in person.

Since neither the internet nor smartphones existed, often the first impression a customer had was through the pen of the commercial illustrator, and his influence really meant something.

Charles Wysocki worked in the automotive field in Detroit for four years. You’ve probably seen his work and not even known it. Once he had worked his way up a little in Detroit, he moved to LA, where he was one of a few who established a new independent ad agency. He worked there as a freelancer.

When he was 32, he met a UCLA art graduate named Elizabeth Lawrence. They were married that same year (1960) in LA. Their lifestyle was a little more rural than that of Detroit and LA, and Charles’ eyes were opened to how beautiful the simple life could be.

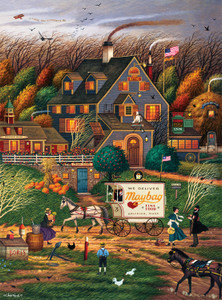

Since Elizabeth and Charles both liked to travel, they took more than a few trips and vacations to the charming New England area, which really inspired Charles’ work. He took a very keen interest in the folk art of early America, but he wasn’t able to concentrate much on developing his own take on it.

He filled his working hours with the lucrative business of his freelance commercial artwork. But Charles still managed to devote some of his spare time to the primitive art forms he had seen and loved in New England. Eventually, his commercial business became so lucrative that he could devote all his time to his Americana work.

Eventually, his primitive artwork was licensed by a firm called AMCAL, Inc., and for a short while, by a company called Greenwich Workshop overseas. Much of his artwork has been rendered as jigsaw puzzles over the years. He has several books to his name, as well as all of the artwork he licensed, which is too numerous to list.

He died on his wedding anniversary in 2002 in Joshua Tree, California, a little desert town just north of Palm Springs. Joshua Tree National Park is nearby, where he no doubt probably enjoyed spending time taking in the stunning desert sunsets. He was survived by his wife and three children.

The Art and the Whimsy

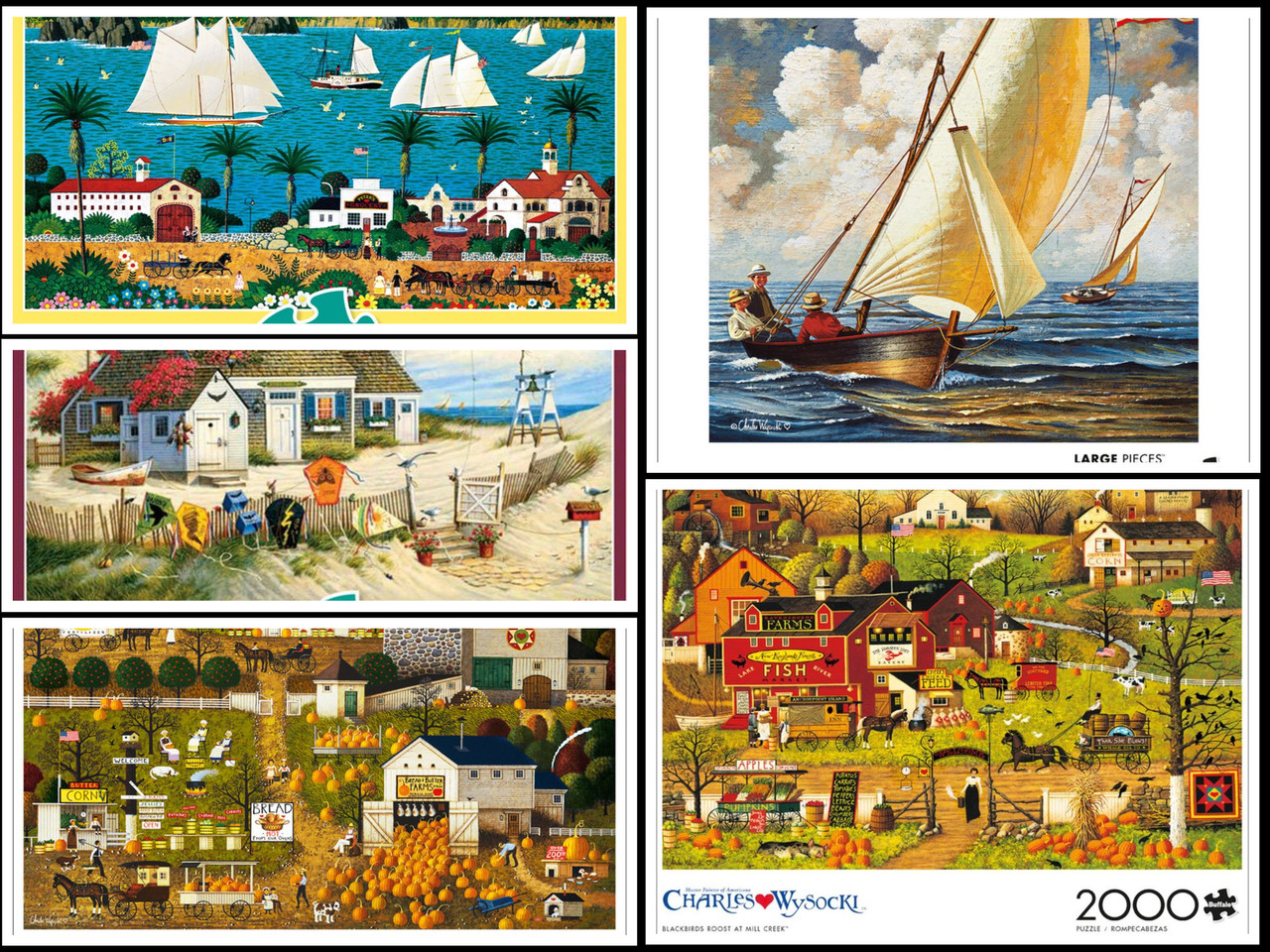

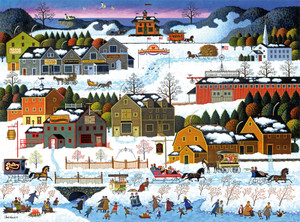

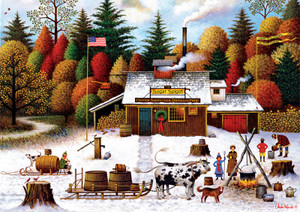

A great example of the early American primitive art he created so beautifully is a puzzle titled “Bread & Butter Farms.”

It is reminiscent of the medieval art that was common before Brunelleschi developed the principle of forced perspective at the dawn of the Italian Renaissance. Brunelleschi, who also built the amazing dome of the Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence, was the genius who first showed three dimensions on the plane of the canvas by drawing the eye into the distance, where the background converged into a single point.

Before Brunelleschi’s innovative approach, all fine art appeared to rest firmly in two dimensions, as it does in Wysocki’s work here. You might think it looks like a child drew it, it’s so simple, but that’s completely on purpose and part of its charm.

For Wysocki, who spent his life trying to make commercial objects look more desirable to the eye, it’s easy to see why this primitive art form drew him in. It’s just plain fun. The colors are bright, the forms are playful and simple, and as it turns out, the results are pretty much perfect for jigsaw puzzles.

Shades of Rockwell

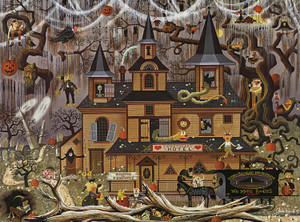

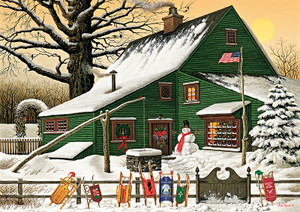

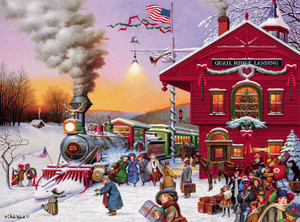

If you’re a puzzler and are looking for something a little closer to what used to grace the cover of The Saturday Evening Post — perhaps something similar to what Norman Rockwell might have produced — take a look at this 300-piece puzzle.

The shading and colors are rich, the perspective really draws you in, and while the message is simple, you won’t tire of looking at this work as you solve it. There are plenty of details and challenges in this puzzle. It’s almost as if Mr. Wysocki was thinking about just where to place each detail to make the perfect painting for a jigsaw puzzle. Like any Wysocki piece, it’s full of whimsy, humor, color, nostalgia, and fancy.

There’s so much fun to be had with these jigsaw puzzles. When you finish a classic Wysocki, you won’t want to take it apart — you’ll want to experience it for a while. And once you’ve done one, you’ll want to keep going. Maybe it would be a worthy goal to see if you could solve every Wysocki puzzle in the collection!